Advocate Varsha Bhogle, partner, Deshmukh Bhogle Legal Associates, linked the rise of legal influencers during the Covid-19-pandemic triggered lockdown restrictions phase, when incidents of marital rape, domestic violence, adultery, and other social ills had become rampant.

The pandemic had also triggered another legal debate amid widespread joblessness and a sudden fall in household incomes due to lack of economic activities. The debate centred on whether tenants should pay their entire monthly rent, deduct a portion or get a blanket waiver during the viral outbreak. However, the decision on this contentious issue boiled down to individual tenancy contracts. So, any form of blanket waiver on monthly rent was found to be infructuous. “All these new aspects of legalities had risen because of the pandemic,” Bhogle said.

Law colleges, like other educational institutions, had remained shut because of the lockdown restrictions. The law students had a lot of time at their disposal and many of them indulged in making reels and videos while attending online classes.

Rise in misinformation and repercussions

The advent of social media and digital platforms, which have democratised dissemination of information, allows legal influencers to share their knowledge with a broader audience. The trend has also resulted in the spread of misinformation, said Amrita S Nair, Advocate, Bombay High Court (HC). She attributed the ill-effects to a lack of expertise or an indulgence in sensationalism to attract more followers on social media.

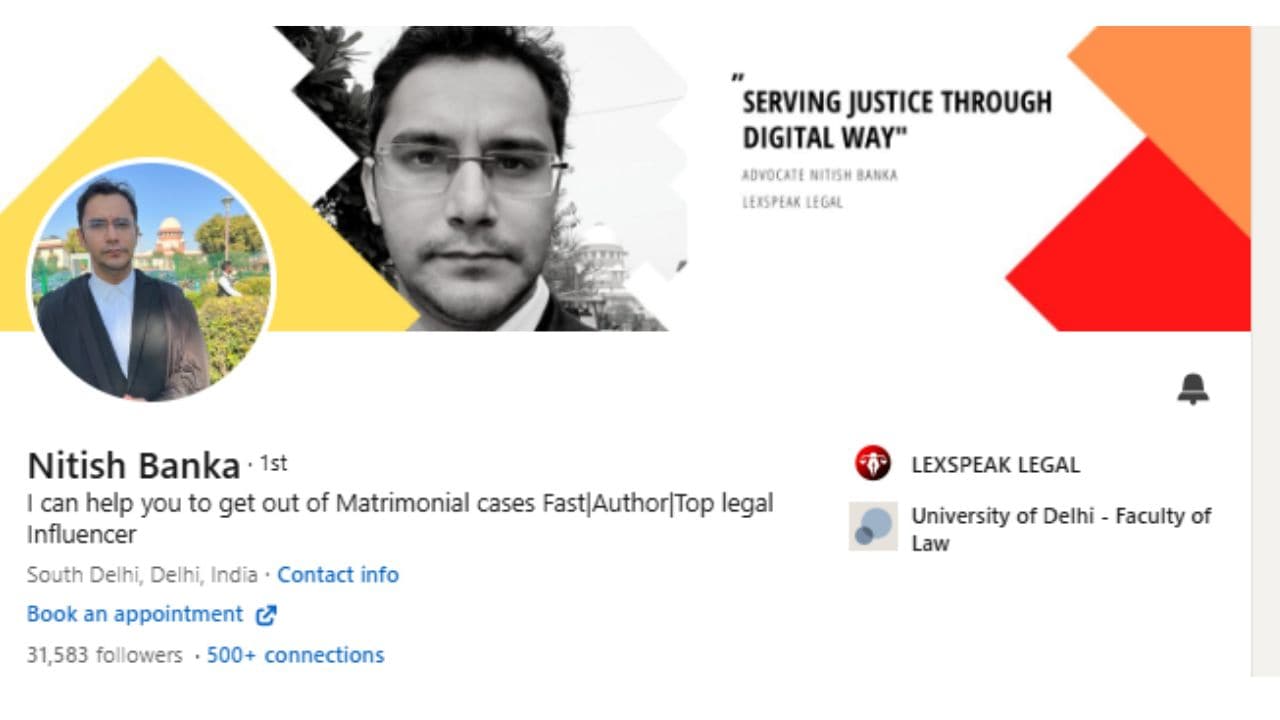

Matrimonial law expert Nitish Banka’s LinkedIn bio is a case in point. The profile claims, “I can help you to get out of Matrimonial cases Fast.” On this, Siddharth Chandrashekhar, advocate & counsel, Bombay HC, stated, “In the case of matrimonial disputes, the minimum amount of time taken is between two and four years. However, I’ve come across cases, which have been going on for over 10 years.”

Akshat Pande, founder and managing partner, Alpha Partners, too, is seized of the matter. He came across a content by a legal influencer that spoke about the process of getting a patent for a product. Pande countered such a claim. “You get a trademark for a brand. However, a patent can only be obtained for an invention,” he said.

According to Nair, when the government implemented the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in 2019, several legal influencers jumped on the bandwagon and put out incorrect interpretations of the Act. Some claimed that the CAA would strip Muslims of their citizenship, causing widespread panic and unrest.

“In reality, the Act offered citizenship to persecuted minorities from neighbouring countries. It did not revoke citizenship of any Indian nationals,” she said.

Nair cites another example of legal misrepresentation such as the Supreme Court’s judgment on the Right to Privacy in the Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India case. Some influencers erroneously suggested that this ruling made all forms of surveillance and data collection by the government illegal. The judgement had affirmed the Right to Privacy as a fundamental right but allowed for reasonable restrictions under certain circumstances.

Nair also highlighted the confusion which centred on the Goods and Services Tax (GST) when it was first introduced on July 1, 2017. Some legal influencers incorrectly stated that certain small businesses were exempt from GST, leading those businesses to neglect registration and compliance. These businesses faced legal hassles and attracted penalties when the authorities enforced the regulations.

When misinformation is identified, taking legal action is cumbersome due to jurisdictional issues, especially when content crosses state or national boundaries, Nair cited. She also pointed out influencers, at times, operate under aliases, making it difficult to trace and hold them accountable for spreading misinformation.

Another major cause of concern: social media platforms may lack stringent policies for vetting legal content, and their algorithms might inadvertently promote sensational or misleading information over accurate but less engaging content.

Perhaps, these influencers are taking advantage of a legal loophole. “The line is blurred between what is legal advice and what is general information,” Bhogle said.

How can the BCI curb these malpractices? The jury is still out on this raging debate on social media and beyond.

(Watch this space for more on ‘The Rise of Legal Influencers in India’)