By Sanjukta Sharma

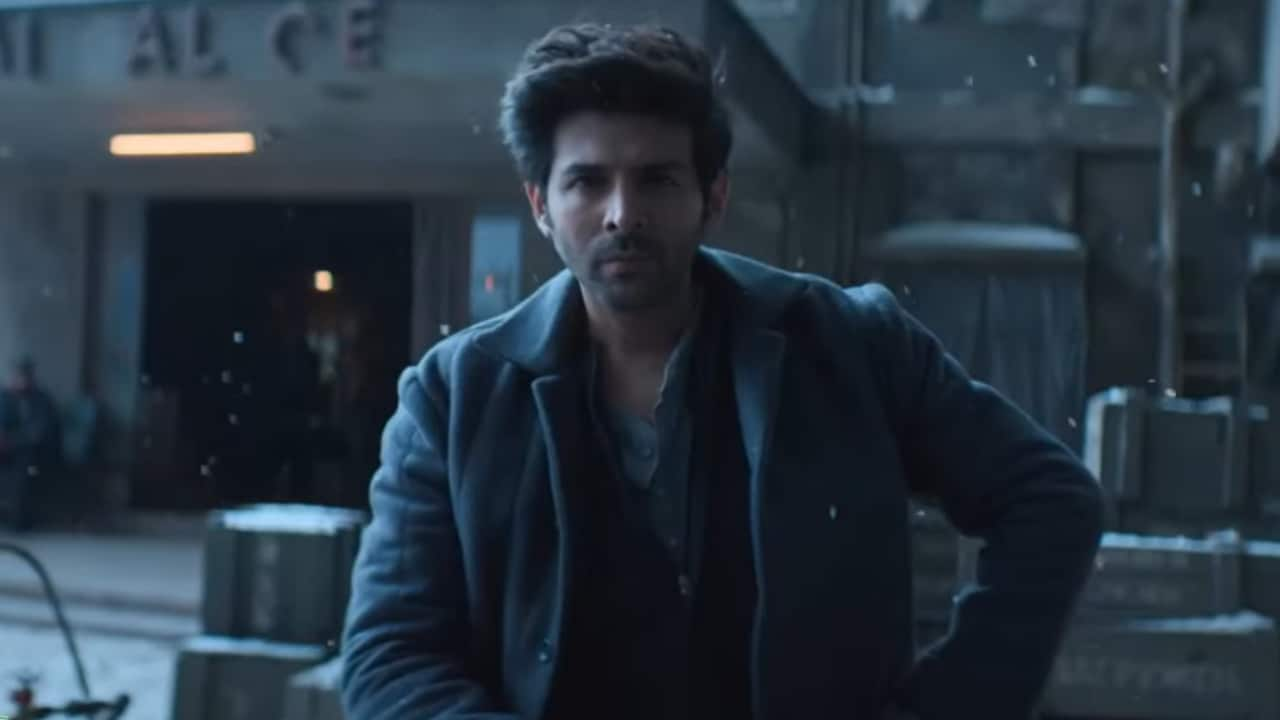

There’s a little bit of all the Bollywood Khans in Kartik Aaryan — it’s difficult to pinpoint which one ends where and which begins where and when the cocktail takes on its own potency. Sometimes it has worked, most of the time, it hasn’t. In his new film, Rohit Dhawan’s Shehzada, a generous amount of Govinda-giri gets thrown in, besides a few improvised Salman Khan platitudes, and you have an actor who seems not only desperate for hits, but keen to bypass innovation and originality for quaint, time-and-tested Bollywood tropes.

This is dinosaur mindset in a world that’s changing literally with every good film that comes out on an OTT player or in theatres. And let’s be clear, if Indian audiences are coming to theatres to see big-scale movies, they don’t mean David Dhawanesque farce and mistaken identity in family dramas. The Dhawan formula worked at a particular time; it’s a twist of pop culture history that it no longer does.

It remains to be seen how Shehzada is received. The film requires heavy-duty love of cheap Bollywood tactics that go back mostly to bad 1980s’ films. Babies separated at birth, master and slave dynamics, the heal-and-fix-all hero who not only wants to claim his pie in a rich family that he lost out on because of his father but tries to heal the toxic family equations that ail his birth family. All in all, Shehzada is primitive drivel. The teenager or the 20-something and certainly the 30-something is too saturated with ideas, visuals, and a dizzying diversity of “content” to be engaged with family dramadies mounted on egotistic scales.

In a career spanning around 12 films starting with Luv Ranjan’s buddy film Pyaar ka Punchnama in 2011, Aaryan has remained faithful to comedy as a genre of choice. Through Pyaar ka Punchnama 2, Sonu ki Titu ki Sweety, Luka Chuppi, Guest iin London, and his most successful film at the box office, Bhool Bhulaiya 2, Aaryan has made it without insider support in Bollywood — he is from Gwalior and started auditioning for films while doing his engineering graduate in Navi Mumbai. Dhamaka for Netflix and Freddy for Disney+ Hotstar — both thrillers, and both attempts at potentially paratrooping Aaryan out of the dull funk of middling Bollywood comedies, backfired, because both these scripts, too, have undue attention to the details of the star — how he appears, how many scenes and monologues he gets, the camera obsessing on his various angles — at the cost of truly bold or original screenplays.

Aaryan has been a teenage heartthrob ever since he emerged a star. His star persona has a cockiness to it, much like the Salman Khan persona. His bromance with director Luv Ranjan, an expert reaper of the romance-meets-comedy genre (as opposed to romantic comedies of Hollywood which has enough trajectories for characters), and with whom Aaryan has done four films, is being tested this year too, with Ranbir Kapoor headlining Ranjan’s forthcoming, Tu Jhoothi Main Makkar (a March 8 release this year) opposite Shraddha Kapoor. Aaryan has always maintained in interviews that he is the “boy next door” — his relationship with the media hasn’t always been breezy, with punctuality always an issue like a star straight from the ’80s, okay, maybe ’90s, and early 2000s too, but you get the point.

But Aaryan himself and those who have backed him as producer, director or writer, haven’t been smart enough to channel “boy next door” with imagination and rigour. The boy next door he represents isn’t a Gen Z Boy Next Door, the new aspiration. At 32, his social media feed is a sameness of pun-fuelled humour and memes. In 2021, Aaryan ranked 20th in Duff & Phelps’s list of India’s most valuable celebrity brands. His reported net worth is around Rs 46 crore, and he charges Rs 15 lakh per television advertisement — besides boAt, Manyavar, Armani Exchange watches, Doritos and Fanta that he endorses, in late 2022, he was signed on as India’s brand ambassador for McDonald’s.

The Kartik Aaryan brand needs serious disruption for it to remain relevant. Thinking at the level of creative storytelling and making him a part of a cinematic universe rather than creating universes for him is, perhaps, a clever starting point.